Norbert Landry - Nellebar Londry

La famille de Norbert Landry du Québec s'installe dans la vallée de Saginaw au Michigan vers 1850.

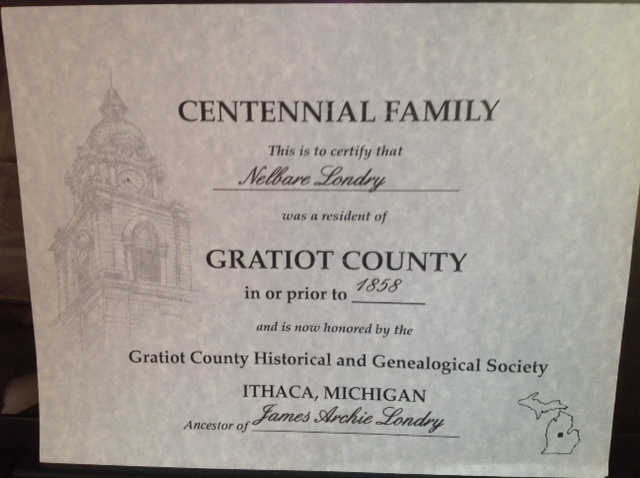

| Norbert Landry s'installe sur une ferme avant 1858. Cette ferme est toujours occupé par la famille Landry. Maintenant par Douglas Londry. | Le comté de Gratiot reconnait que la famille de Norbert Landry (Nelbare Londry) est sur cette cette ferme depuis au moins 1858. |

|

|

|

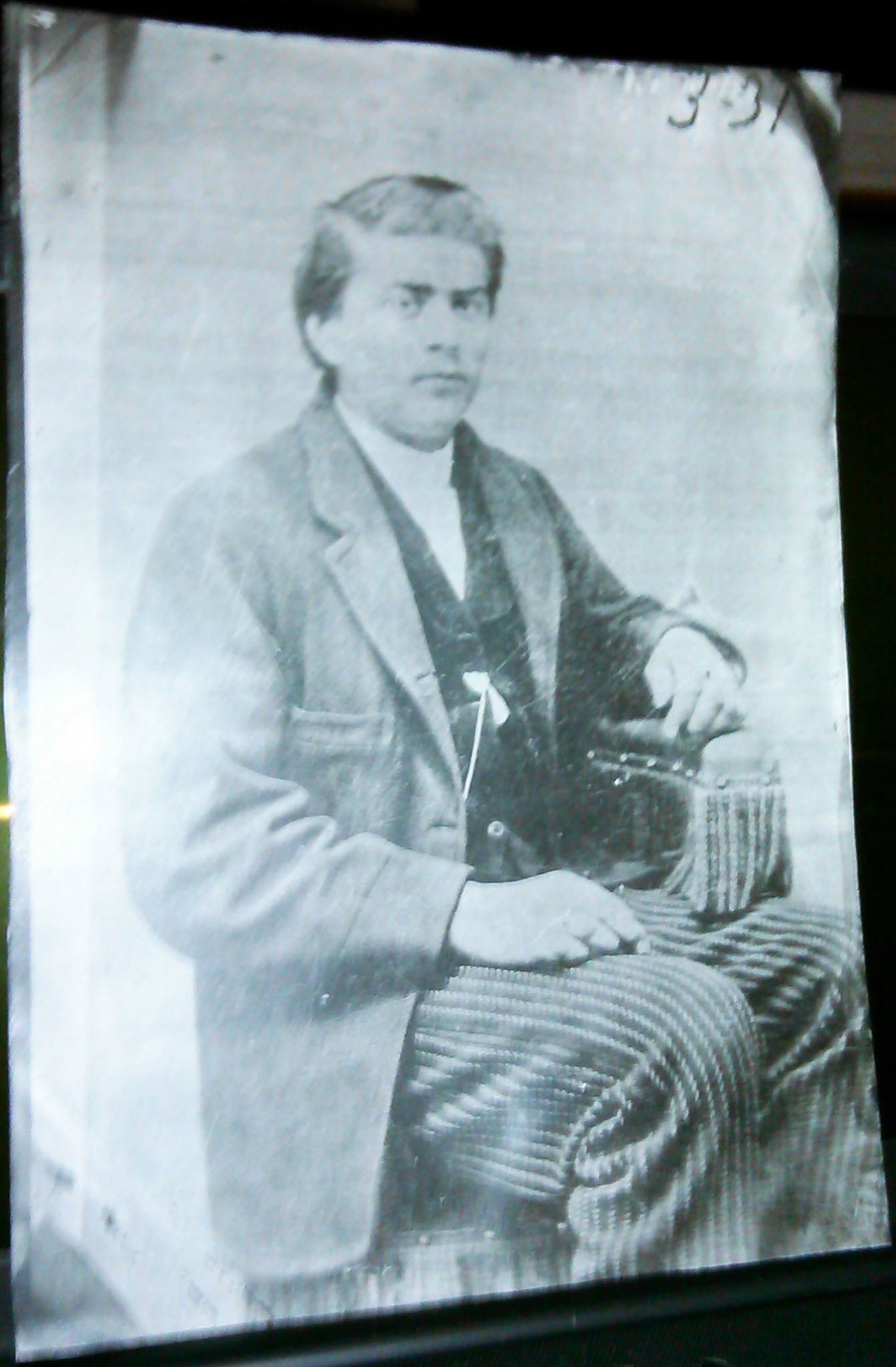

| Photo de Norbert Landry sur métal (tintype) vers 1865. |

|

| Documents, en 2014 gracieuseté de Douglas Londry de Saginaw au Michigan. |

Article sur Norbert publié le 11 juillet 2019, gracieuseté de Douglas Londry et le Gratiot County Herald du Michigan.

|

| Thursday, July 11, 2019 Gratiot County Herald - Page 3 |

| Family Historian Leaves No

Stone Unturned Great-Great-Grandson Honors Civil War Vet With Proper Headstone |

|

Civil War vet and early Gratiot County settler Nellebar Londry. (Courtesy of Douglas Londry)

The new Civil War headstone was installed by Londry and members of the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War in June. (Herald photo - Selmon)

Londry’s father James, far right, on the battlefield in North Korea in 1951 with South Korean soldiers. (Courtesy of Douglas Londry)

Londry’s house in Lafayette Township, built by his great-grandfather in 1899. (Herald photo - Selmon) |

by Emma Selmon

Nellebar Londry, a Civil War

veteran and early settler of Lafayette Township, now has a headstone

identifying his name and recognizing his service, thanks to the efforts of

his great-great-grandson, Douglas Londry. Londry has kept himself busy as a family historian over the years. Obtaining the headstone from the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War (SUVCW) was the last step in the process that he started with his late father, James, 15 years ago. With the help of the SUVCW, Londry was able to fill in some of the blanks in his family history — and leave a lasting memorial to the man who sacrificed so much for his family and his country.

In attempts to help Nellebar

secure his disability pension, several of his neighbors — many of whom are

buried nearby Nellebar — wrote letters to the VA on his behalf. One neighbor, William Easlick,

wrote that Nellebar “has been almost totally disabled from performing manual

labor on account of Rheumatism disease of heart and eyes.” Another, Otto

Schirmer, assured the VA “that [Nellebar] has no vicious habits & that he is

a temperate man.” Despite the kind gestures of his

neighbors, Nellebar died in 1896 without having received any disability “I was told it was when they

ordered the stone, the guy did it wrong,” he said. “Our name was Landry,

but…they just wrote it down like it sounded: Laundry.” Though Nellebar’s grave lacked a

proper marker, his legacy lived on through his children. His son, Londry’s

great-grandfather, built a house on Nellebar’s farm in 1899 that still

stands today. And Londry’s grandfather, Mike, followed in his grandfather’s

military footsteps to enlist in WWI. While parts of Nellebar’s life

had been a mystery, Mike Londry’s When he enlisted in July 1918 at

23 years old, Mike was shipped to Archangel, Russia as a member of the

famous “Polar Bear” unit. Although the WWI fighting officially ended on

Armistice Day — November 11, 1918 — the “Polar Bear” unit found themselves

stranded in the Russian winter, Londry said. They ended up fighting the

Bolsheviks in the Russian Revolution all winter before they were finally

able to leave in the spring, when the waterways thawed. After returning from the war,

Mike Londry had four sons, all of whom were involved in the military.

Londry’s uncle Bill enlisted in the Navy in 1942, where he was stationed in

Hawaii to help rebuild Pearl Harbor. His uncle Thomas served on the Patrol

Torpedo (PT) boats in the Pacific alongside future president John F.

Kennedy. Londry’s father James was drafted

into the army in 1950 and and was sent to North Korea, where he fought with

the 7th Calvary, “right during the heavy fighting when the Chinese were

there,” Londry said. And Londry’s youngest uncle Lester joined the navy in

1955. From the Civil War to Korea and

through all of the “hardships” they experienced, each of Londry’s family

members made it back home. And through it all, the homestead that Nellebar

founded remained. Today, Londry lives where he grew

up —on the farm his great-great-grandfather cleared, in the house that his

great-grandfather built, and nearby Lafayette Cemetery where much of his

family is buried. Londry is the fifth generation to live on the farm, and

should his son and granddaughter chose to live there someday, they would be

the sixth and seventh generations. Londry is “proud” to have

finished what he and his father started, |

Source: gcherald.com/pdf/7-11-19.pdf 15 jul 2019

Dernière modification : samedi 08 novembre 2025